A rose y any other name would smell as sweet

16.07.2022 – 31.07.2022

Light: the medium through which everything, including a work of art, is visible.

Without light there is no image; without light we see nothing.

But what if we want to depict light? By which I don’t mean the representation of the effect of light, such as in Impressionist sunsets or Baroque chiaroscuro scenes, but light itself. What could be an accurate visual representation of light? How to create an image that – essentially – captures light as it is? Greet Billet has been pondering this question for years, and has presented several proposals that do justice to both the simplicity and complexity of the matter.

Assuming the computer could offer an “objective” image – i.e. with no human interference – she began her quest with the translation of a digital byte, the smallest usable information unit in a computer that can be converted into something visible for the human eye, into an analog form. As a byte consists of 8 bits, and a bit being 0 or 1, one byte has 256 “patterns” or possible combinations of ones and zeros. Billet translated the byte data of four particu- lar colors into four series of screen prints on paper, each containing 256 shades of one color: the first going from black to white; the next going from black to red, green and blue respectively—representing “RGB,” the additive color model used in electronic devices.

This translation from digital to analog resulted in an appealing color series, spread open in an installation, or piled up, presented as a thick book. Nevertheless, when it came to the element of light itself, the artist found the art works lost power. Therefore, as a next step in the re- search process and inspired by Umberto Eco’s book On Mirrors and Other Essays (originally published in Italian in 1985), she (re)introduced the mirror in her work. For, ac- cording to Eco, the mirror does not interpret the things it represents but merely reflects them. The depersonalized reflection of light, which the mirror offered, was exactly what Greet Billet was looking for. The mirror represents light, color and its surroundings “truthfully” particularly because it captures their constant evolution. No other medium or action by the hand of the artist could do that more accurately. Even when moving, the mirror keeps this capacity, as Billet showed in `There is No Seduction (2019)`. There, two large, circular mirrors – one of them being carelessly painted in white – were (engine-driven) slowly rotating. Whereas the painted mirror was clearly rotating, the movement of the unpainted mirror was barely visible to the viewer due to the rounded shape of the object. It continued to show a reliable, recognizable image of the environment.

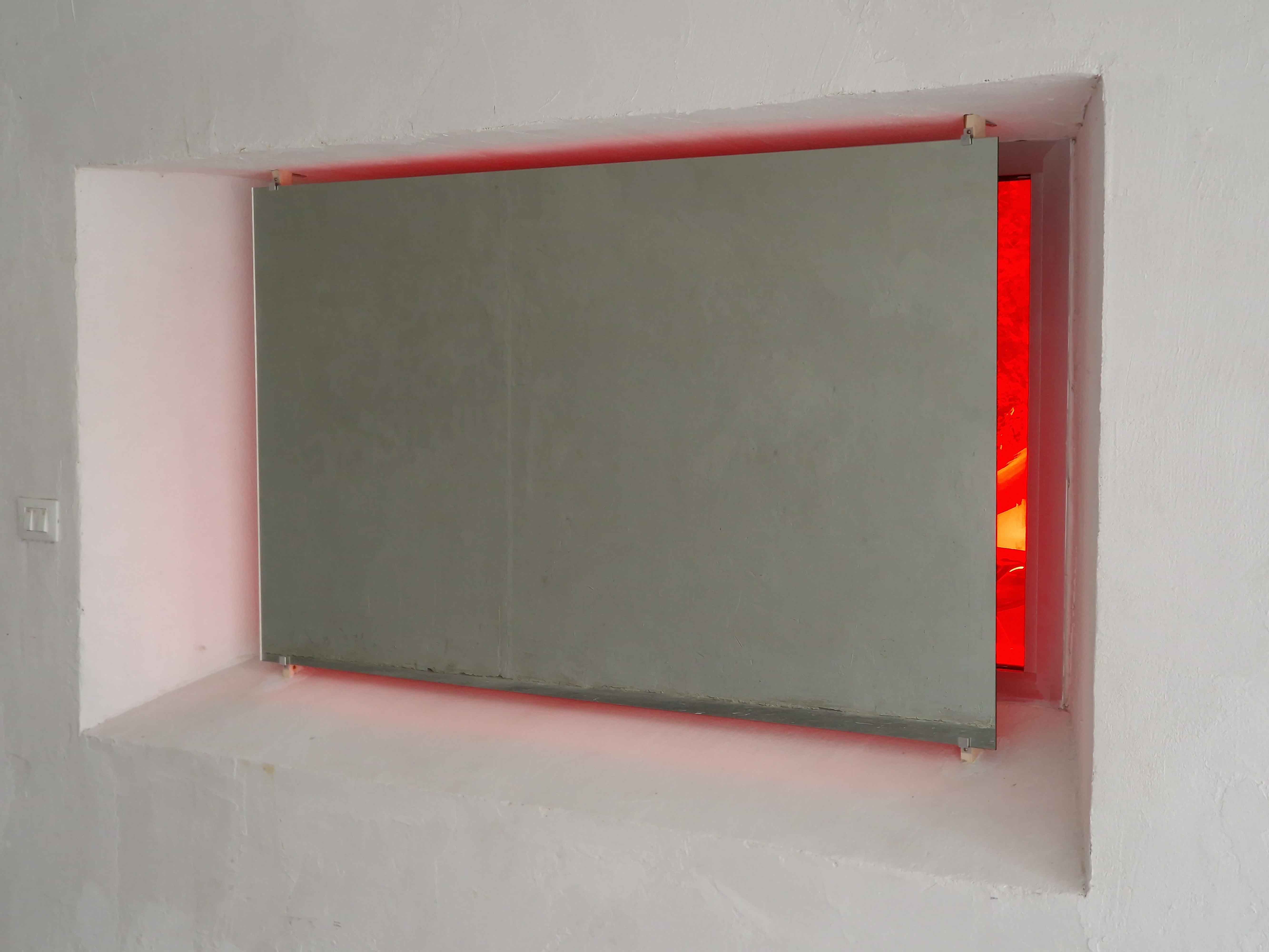

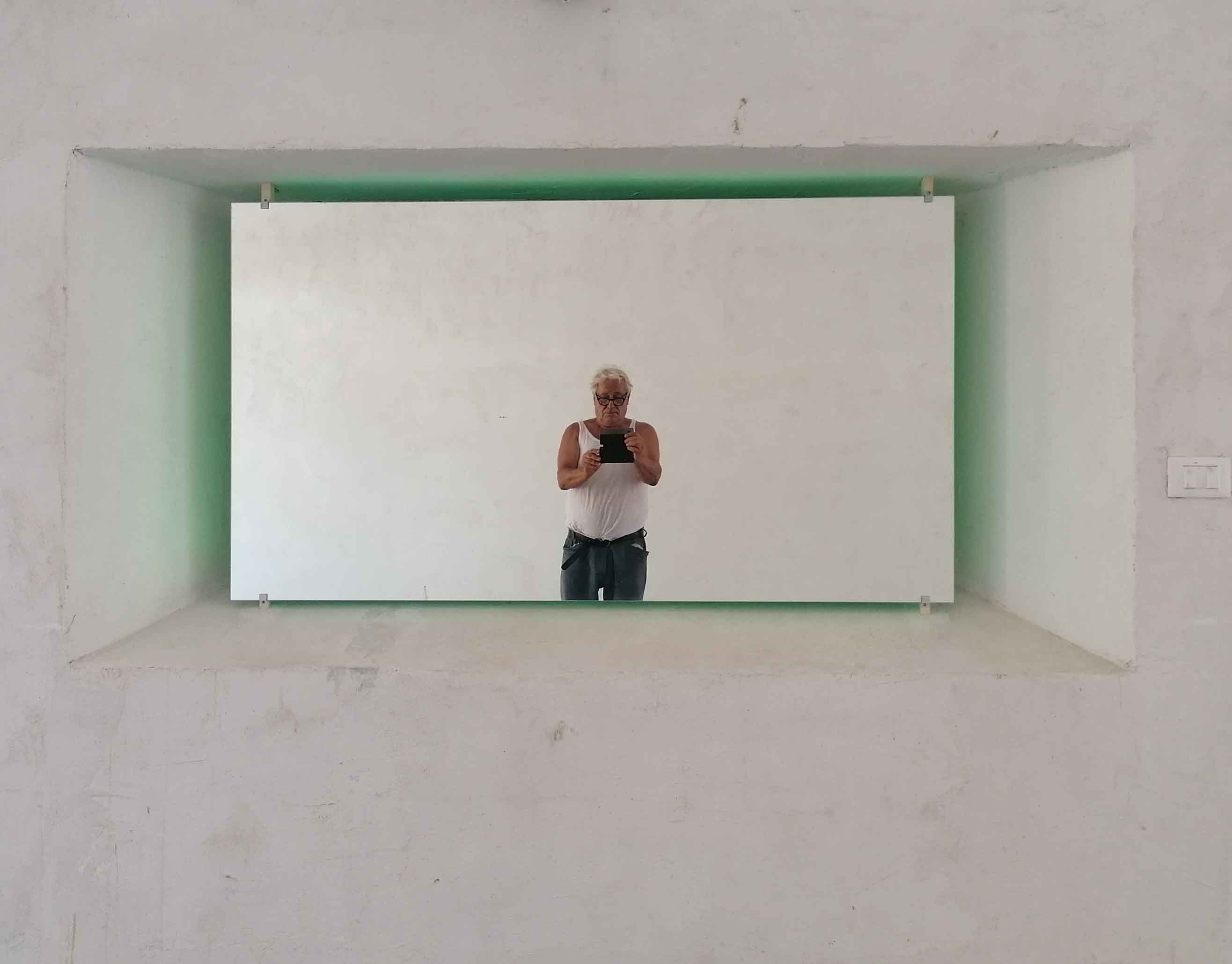

Greet Billet also used foil and Plexiglas to visualize light. Just like the mirror these materials are industrially produced, thus excluding any subjective intervention by the artist, and they also have a reflecting surface, especially when several layers are placed on top of each other. In addition, they are available in various colors, provid- ing the artist with the opportunity to work once again with the basic color compo- nents of light: “RGB” (the primary colors of light – Red, Green and Blue – as used in digital media) and “CMYK” (referring to the primary colors of pigment: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black). Billet plays with the effect of blending colors by layering differ- ent color sheets; or just unravels the color groups by showing one single sheet. Using the tactile characteristics of both media, she presents the firm Plexi sheets on the floor, leaning against the wall. The flexible foils are hanging on a rod, which is attached to the wall, or – as a freestanding sculpture – on a stand that is traditionally used to create backgrounds in a photo studio.

The installations with foil and Plexi, often es- pecially designed for a specific site, reflect their surroundings, including the visitors of the space, in a distorted way. This makes the viewer very conscious about his/her presence in the room and interaction with the art work. Every move he/she makes changes his/her perception of the work.

The works also capture the light, and in a space with natural light, the intensity of the colors changes according to the weather conditions and the time of the day. In bright sunlight, for example, the foil sheets appear very light (both in terms of weight and color tone), while when night falls they can appear thick, heavy and viscous.

The use of reflective materials proves es- sential in Greet Billet’s attempts to visualize light. However, the key to capturing light also lies in the repetition of the action: displaying the light over and over again, through the mirroring materials, always adapted to the space in which they are situated. Thus, the artist exposes the constantly changing conditions of light and its surroundings, and shows that, in fact, light never truly allows itself to be captured.

Liesbeth Decan July 2022

Lumière : le médium à travers lequel tout, y compris une œuvre d’art, est visible. Sans lumière, il n’y a pas d’image ; sans lumière on ne voit rien.

Mais que se passe-t-il si nous voulons représenter la lumière ? Je n’entends pas par là la représentation de l’effet de la lumière, comme dans les couchers de soleil impressionnistes ou les scènes de clair-obscur baroque, mais la lumière elle-même. Quelle pourrait être une représentation visuelle précise de la lumière ? Comment créer une image qui – essentiellement – capture la lumière telle qu’elle est ? Greet Billet réfléchit à cette question depuis des années et a présenté plusieurs propositions qui rendent justice à la fois à la simplicité et à la complexité de la question.

Partant du principe que l’ordinateur pouvait offrir une image “objective” – c’est-à-dire sans interférence humaine – elle a commencé sa quête par la traduction d’un octet numérique, la plus petite unité d’information utilisable dans un ordinateur qui peut être convertie en quelque chose de visible pour l’œil humain, en une forme analogique. Comme un octet se compose de 8 bits, et qu’un bit vaut 0 ou 1, un octet a 256 “motifs” ou combinaisons possibles des uns et de zéros. Billet a traduit les données en octets de quatre couleurs particulières en quatre séries de sérigraphies sur papier, chacune contenant 256 nuances d’une couleur : la première allant du noir au blanc ; le suivant allant respectivement du noir au rouge, au vert et au bleu, représentant « RGB », le modèle de couleur additif utilisé dans les appareils électroniques.

Cette traduction du numérique à l’analogique a donné lieu à une séduisante série de couleurs, déployées à découvert dans une installation, ou empilées, présentées comme un livre épais. Néanmoins, en ce qui concerne l’élément de lumière lui-même, l’artiste a constaté que les œuvres d’art avaient perdu leur pouvoir. Par conséquent, comme étape suivante dans le processus de recherche et inspirée par le livre d’Umberto Eco On Mirrors and Other Essays (initialement publié en italien en 1985), elle a (ré)introduit le miroir dans son travail. Car, selon Eco, le miroir n’interprète pas les choses qu’il représente mais se contente de les refléter. Le reflet dépersonnalisé de la lumière, qu’offrait le miroir, était exactement ce que Greet Billet recherchait. Le miroir représente « fidèlement » la lumière, la couleur et son environnement notamment parce qu’il capte leur constante évolution. Aucun autre médium ou action de la main de l’artiste ne pourrait le faire avec plus de précision. Même en mouvement, le miroir conserve cette capacité, comme Billet l’a montré dans `There is No Seduction (2019)`. Là, deux grands miroirs circulaires – l’un d’eux étant négligemment peint en blanc – tournaient lentement (entraînés par un moteur). Alors que le miroir peint tournait clairement, le mouvement du miroir non peint était à peine visible pour le spectateur en raison de la forme arrondie de l’objet. Il a continué à montrer une image fiable et reconnaissable de l’environnement.

Greet Billet a également utilisé du papier d’aluminium et du plexiglas pour visualiser la lumière. Tout comme le miroir, ces matériaux sont fabriqués industriellement, excluant ainsi toute intervention subjective de l’artiste, et ils possèdent également une surface réfléchissante, surtout lorsque plusieurs couches sont superposées. De plus, ils sont disponibles en différentes couleurs, offrant à l’artiste l’opportunité de retravailler avec les composantes de base de la couleur de la lumière : “RVB” (les couleurs primaires de la lumière – Rouge, Vert et Bleu – telles qu’utilisées dans les médias numériques) et “CMJN” (faisant référence aux couleurs primaires du pigment : cyan, magenta, jaune et noir). Billet joue sur l’effet de mélange des couleurs en superposant différentes feuilles de couleurs ; ou démêle simplement les groupes de couleurs en affichant une seule feuille. Utilisant les caractéristiques tactiles des deux médias, elle présente les feuilles de plexi fermes au sol, appuyées contre le mur. Les feuilles flexibles sont suspendues à une tige fixée au mur ou, en tant que sculpture autoportante, à un support traditionnellement utilisé pour créer des arrière-plans dans un studio photo.

Les installations avec film et plexi, souvent spécialement conçues pour un site précis, reflètent leur environnement, y compris les visiteurs de l’espace, de manière déformée. Cela rend le spectateur très conscient de sa présence dans la pièce et de son interaction avec l’œuvre d’art. Chaque geste qu’il fait modifie sa perception de l’œuvre.

Les œuvres captent également la lumière, et dans un espace à la lumière naturelle, l’intensité des couleurs change en fonction des conditions météorologiques et de l’heure de la journée. En plein soleil, par exemple, les feuilles d’aluminium apparaissent très légères (à la fois en termes de poids et de tonalité de couleur), tandis que lorsque la nuit tombe, elles peuvent apparaître épaisses, lourdes et visqueuses.

L’utilisation de matériaux réfléchissants s’avère essentielle dans les tentatives de Greet Billet de visualiser la lumière. Cependant, la clé de la capture de la lumière réside également dans la répétition de l’action : afficher la lumière encore et encore, à travers les matériaux miroirs, toujours adaptés à l’espace dans lequel ils se trouvent. Ainsi, l’artiste expose les conditions sans cesse changeantes de la lumière et de son environnement, et montre qu’en fait, la lumière ne se laisse jamais véritablement capter.

Liesbeth Decan Juillet 2022

Luce: il mezzo attraverso il quale tutto, compresa un’opera d’arte, è visibile. Senza luce non c’è immagine; senza luce non vediamo niente.

Ma cosa succede se vogliamo rappresentare la luce? Con ciò non intendo la rappresentazione dell’effetto della luce, come nei tramonti impressionisti o nei chiaroscuri barocchi, ma la luce stessa. Quale potrebbe essere una rappresentazione visiva accurata della luce? Come creare un’immagine che – essenzialmente – catturi la luce così com’è? Greet Billet ha riflettuto su questa domanda per anni e ha presentato diverse proposte che rendono giustizia sia alla semplicità che alla complessità della questione.

Partendo dal presupposto che il computer potesse offrire un’immagine “oggettiva”, cioè senza interferenza umana, ha iniziato la sua ricerca con la traduzione di un byte digitale, la più piccola unità di informazione utilizzabile in un computer che può essere convertita in qualcosa di visibile all’occhio umano, in una forma analogica. Poiché un byte è composto da 8 bit e un bit è 0 o 1, un byte ha 256 “modelli” o possibili combinazioni di uno e zero. Billet ha tradotto i dati in byte di quattro particolari colori in quattro serie di serigrafie su carta, ciascuna contenente 256 sfumature di un colore: la prima va dal nero al bianco; il successivo va rispettivamente dal nero al rosso, al verde e al blu, rappresentando “RGB”, il modello di colore additivo utilizzato nei dispositivi elettronici.

Questa traduzione dal digitale all’analogico ha prodotto una serie di colori accattivanti, sparsi in un’installazione o ammucchiati, presentati come un grosso libro. Tuttavia, quando si trattava dell’elemento della luce stessa, l’artista ha scoperto che le opere d’arte avevano perso potere. Pertanto, come passo successivo nel processo di ricerca e ispirandosi al libro di Umberto Eco `On Mirrors and Other Essays` (pubblicato originariamente in italiano nel 1985), ha (re)introdotto lo specchio nel suo lavoro. Perché, secondo Eco, lo specchio non interpreta le cose che rappresenta, ma semplicemente le riflette. Il riflesso spersonalizzato della luce, offerto dallo specchio, era esattamente ciò che Greet Billet stava cercando. Lo specchio rappresenta la luce, il colore e ciò che lo circonda “veramente”, soprattutto perché ne cattura la costante evoluzione. Nessun altro mezzo o azione della mano dell’artista potrebbe farlo in modo più accurato. Anche quando si muove, lo specchio mantiene questa capacità, come ha mostrato Billet in “Non c’è seduzione (2019)”. Lì, due grandi specchi circolari, uno dei quali dipinto di bianco con noncuranza, ruotavano lentamente (azionati dal motore). Mentre lo specchio dipinto ruotava chiaramente, il movimento dello specchio non dipinto era appena visibile all’osservatore a causa della forma arrotondata dell’oggetto. Ha continuato a mostrare un’immagine affidabile e riconoscibile dell’ambiente.

Greet Billet ha anche utilizzato lamina e plexiglas per visualizzare la luce. Proprio come lo specchio questi materiali sono prodotti industrialmente, escludendo quindi ogni intervento soggettivo dell’artista, e hanno anche una superficie riflettente, soprattutto quando si sovrappongono più strati. Inoltre, sono disponibili in vari colori, offrendo all’artista la possibilità di lavorare ancora una volta con le componenti cromatiche di base della luce: “RGB” (i colori primari della luce – Rosso, Verde e Blu – come usati nei media digitali) e “CMYK” (riferito ai colori primari del pigmento: ciano, magenta, giallo e nero). Billet gioca con l’effetto di sfumare i colori sovrapponendo fogli di diversi colori; o semplicemente svela i gruppi di colori mostrando un singolo foglio. Utilizzando le caratteristiche tattili di entrambi i supporti, presenta le solide lastre Plexi sul pavimento, appoggiate al muro. Le lamine flessibili sono appese a un’asta fissata al muro o, come scultura autoportante, a un supporto tradizionalmente utilizzato per creare sfondi in uno studio fotografico.

Le installazioni con foil e plexi, spesso progettate appositamente per un sito specifico, riflettono l’ambiente circostante, compresi i visitatori dello spazio, in modo distorto. Questo rende lo spettatore molto consapevole della sua presenza nella stanza e dell’interazione con l’opera d’arte. Ogni mossa che fa cambia la sua percezione del lavoro.

Le opere catturano anche la luce e, in uno spazio con luce naturale, l’intensità dei colori cambia a seconda delle condizioni meteorologiche e dell’ora del giorno. Alla luce del sole, ad esempio, i fogli di alluminio appaiono molto leggeri (sia in termini di peso che di tonalità di colore), mentre quando scende la notte possono apparire spessi, pesanti e viscosi.

L’uso di materiali riflettenti si rivela essenziale nei tentativi di Greet Billet di visualizzare la luce. Ma la chiave per catturare la luce sta anche nella ripetizione dell’azione: mostrare la luce più e più volte, attraverso i materiali specchianti, sempre adattati allo spazio in cui si trovano. Così, l’artista espone le condizioni in costante mutamento della luce e dell’ambiente circostante, e mostra che, in effetti, la luce non si lascia mai veramente catturare.

Liesbeth Decan luglio 2022